Bhauiputahang dynasty

King Bhauiputahang of Limbuwan was a significant figure in the history of Nepal, reigning as the first independent king of Limbuwan around 580 BC. During this period, a notable event unfolded when King Jitedasti became the seventh Kirant king in central Nepal. The Yakthung chiefs residing in the Limbuwan region decided to rebel against King Jitedasti, no longer acknowledging him as their supreme ruler. This rebellion marked a pivotal moment as it disrupted the traditional system where all Kirant chiefs paid tribute in the form of monetary contributions and provided military service to the Kirant kings based in the Kathmandu valley.

The dynamics within the Kirant society at that time were reminiscent of feudal structures seen in medieval Europe, characterized by hierarchical relationships and obligations between the rulers and subjects. Following the revolts in the Limbuwan area, the Yakthung chiefs made a significant decision by electing Bhauiputahang as their new king, with his capital established in the strategic location of Phedap. King Bhauiputahang assumed rulership over eastern Limbuwan, a territory encompassing what is now modern-day Nepal, thereby solidifying his authority and influence in the region.

It is fascinating to note the parallel development of different dynasties in Nepal during this era. While central Nepal was under the rule of the Kirant dynasty, the Yakthung dynasty governed Limbuwan in the eastern part of the country. The contrasts between King Bhauiputahang’s reign in the east and King Jitedasti’s rule in the Kathmandu valley highlight the diverse political landscape and power structures within Nepal at that time. King Bhauiputahang’s reputation extended far beyond Limbuwan, earning him recognition and respect across eastern Nepal due to his leadership and governance. In comparison, King Jitedasti maintained his authority within the confines of the Kathmandu valley, showcasing the regional variations in political control and influence during this period.

This historical context not only sheds light on the intricate relationships between different kingdoms and rulers in ancient Nepal but also underscores the complexities of power dynamics and leadership transitions that shaped the region’s history. King Bhauiputahang’s ascension to the throne and establishment of his reign in eastern Limbuwan symbolize a pivotal moment in the region’s history, demonstrating how shifts in leadership and alliances could redefine the political landscape and influence the course of events in Nepal. The narratives surrounding King Bhauiputahang and King Jitedasti serve as compelling reminders of the rich heritage and diverse historical tapestry that define Nepal’s past, offering valuable insights into the evolution of governance and authority in the region.

King Parbatakhang, a significant figure in the history of Limbuwan, ascended to power around 317 BC as the son of King Jeitehang and a descendant of King Bhauiputahang. His reign marked a pivotal era in the Himalayan Limbuwan region and what is now known as Nepal, where he held a position of unrivaled strength and authority. Notably, King Parbatakhang formed a strategic alliance with the formidable Chandra Gupta Maurya of the Magadha Empire, a shrewd move that greatly influenced the political landscape of the time.

During this period, King Parbatakhang played a crucial role in supporting Chandra Gupta Maurya in his military endeavors, particularly in campaigns against the Nanda Kingdom and the Greek Satraps who had established their dominance in Punjab and Sindh following Alexander the Great’s invasion of India. King Parbatakhang’s military prowess and strategic acumen were vital in assisting Chandra Gupta Maurya in driving the Greek Satraps, particularly Seleucus the military governor, out of the regions of Punjab and Sindh, thereby securing these territories for the Maurya Empire.

In recognition of King Parbatakhang’s invaluable contributions and steadfast loyalty, Chandra Gupta Maurya rewarded him with extensive lands in the northern region of Bihar. This gesture not only solidified the bond between the two rulers but also led to a significant migration of Kirant people from Limbuwan to northern Bihar, where they came to be known as the Madhesia Kirant people. The presence of these Kirant settlers in Bihar further strengthened the ties between King Parbatakhang’s realm and the expanding Maurya Empire, contributing to the cultural exchange and integration between the Himalayan region and the heartland of the Mauryan dynasty.

In historical records preserved by Magadha historians, King Parbatakhang emerges as a notable ally of the Maurya Empire, his name intertwined with the narrative of Chandra Gupta Maurya’s triumphs and territorial expansions. Through his strategic alliances, military prowess, and diplomatic finesse, King Parbatakhang left an enduring legacy in the annals of both Limbuwan history and the broader context of ancient Indian civilizations. His legacy as a respected and influential ruler resonates through the accounts of his contributions to the rise and consolidation of the Maurya Empire, underscoring his pivotal role in shaping the political dynamics of his time and leaving an indelible mark on the tapestry of South Asian history.

After seven generations of King Parbatakhang, an era of change came to Limbuwan in Eastern Nepal when King Samyukhang ascended the throne. His rule was met with discontent among the descendants of the Madhesia Kirant people, the lineage tracing back to those who resided in Bihar during the reign of King Parbatakhang. Rising against the perceived tyranny of King Samyukhang, the community rallied under the leadership of Bazdeohang, embarking on a courageous journey to challenge the status quo. Through united efforts and unwavering determination, the populace succeeded in overthrowing King Samyukhang, creating a shift in power dynamics within Limbuwan. In the wake of this monumental revolution, the Yakthung chiefs found themselves at a pivotal moment, faced with the choice of determining the future leadership. Following intricate deliberations and reflective considerations, Bazdeohang emerged as the consensual choice to fill the void left by the ousted monarch, stepping into the role as the new king (Hang) of Limbuwan. Thus, a new chapter unfolded in Limbuwan’s history, marked by upheaval, resilience, and the intrinsic quest for justice and governance.

Bazdeohang Dynasty

After the revolution led by the Yakthung people in the Limbuwan region, the chiefs of the community made the significant decision to elect Bazdeohang as their king. Bazdeohang, a former rebel leader, became the central figure in establishing a new era with his ascension to the throne. Moving the capital to Libang marked the beginning of the Bazdeohang Dynasty, a lineage that would see a total of twelve rulers from within the family.

The first in line after Bazdeohang was King Sangkhadeo Hang I, who carried forward the legacy with a strong sense of purpose and governance. Following him, King Sangkhadeo Hang II continued to build upon the foundations laid by his predecessor, ensuring stability and progress for the kingdom. King After the revolution of the Yakthung people of Limbuwan area, the Yakthung chiefs of the region elected the rebel leader Bazdeohang as their king (Hang). He made his capital at Libang and started his own dynasty. He was followed by twelve other kings (Hangs) of his dynasty, each contributing to the rich history of the Bazdeohang Dynasty that spanned over centuries.

The lineage of the kings included Bazdeohang’s successors:

– King Sangkhadeo Hang I, known for his strategic prowess and diplomatic skills.

– King Sangkhadeo Hang II, who expanded the kingdom’s boundaries through alliance-building with neighboring territories.

– King Dewapour Hang, who promoted cultural and artistic expressions within the kingdom, leaving a lasting legacy of creativity.

– King Bhichuuk Hang, a warrior king who successfully defended the kingdom against external threats and invaders.

– King Ghangtuk Hang, the king who initiated major infrastructural developments that improved the lives of his subjects.

– King Sotumhang Hang, a ruler revered for his wisdom and fair governance that brought prosperity to the kingdom.

– King Limdung Hang, a monarch known for his dedication to the well-being of his people and introduction of social welfare programs.

– King Lijehang Hang, who strengthened the kingdom’s military prowess and secured peace within its borders.

– King Mapunhang Hang, a visionary ruler who encouraged trade and commerce, establishing Limbuwan as a hub of economic activity.

– King Dendehang Hang, a reformer who implemented progressive policies for the betterment of society, leaving a lasting impact.

– King Kundungjapa Hang, the penultimate ruler of the Bazdeohang Dynasty known for his statesmanship and diplomatic acumen in maintaining stability.

The lineage reached its culmination with the last king of the Bazdeohang dynasty, who had four sons: Mundhungge Hang, Sandhungge Hang, Kane Hang, and Kochu Hang. Legend has it that Kochu Hang ventured to North Bengal, establishing the kingdom of Kochpiguru, which later became synonymous with the term “Koch.” Sadly, after the demise of King Kundungjapa, the once-prosperous Limbuwan descended into chaos and anarchy, with individual chiefs ruling over fragmented regions, marking the end of an era of unity and prosperity under the Bazdeohang Dynasty.

The era of ten Limbu kings

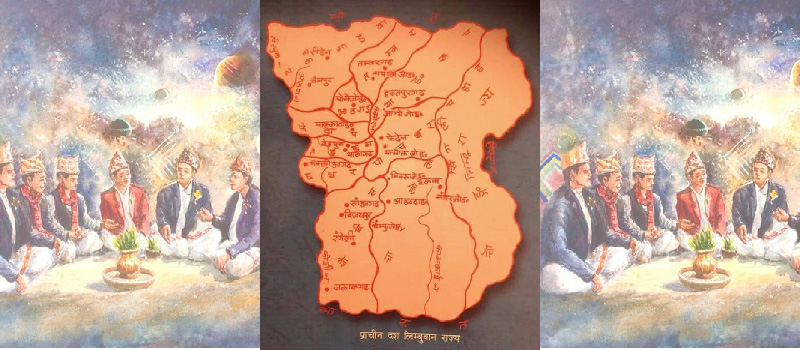

During the era of ten Limbu kings, spanning from 550 to 1609 AD, the Yakthung leaders exhibited remarkable unity and strength in establishing fixed boundaries for Limbuwan. These boundaries extended from the northern reaches touching Tibet, the southern limits near JalalGarh in Bihar, the eastern frontier tracing the course of the river Teesta, to the western extent embracing the Dudhkoshi River. Over time, the territorial boundaries of Limbuwan underwent further delineation, settling at the western banks of the Arun river and against the majestic backdrop of the Kanchenjunga mountain with the Mechi river marking the eastern boundary.

A pivotal meeting of rebel leaders led to the christening of the newly acquired land as Limbuwan, symbolizing its conquest through the might of a bow and arrow (Li meaning “bow” and ambu signifying “acquire” in the Limbu language). To govern this land more effectively, the decision was made to partition Limbuwan into ten districts or kingdoms, each to be ruled by a designated king.

The ten distinguished Limbu rulers, along with their respective territories and fortified capitals, were as follows:

1. Samlupi Samba Hang – reigning over Tambar with his capital at Tambar Yiok.

2. Sisigen Sireng Hang – governing the Mewa and Maiwa kingdoms from his majestic capital, Meringden Yiok.

3. Thoktokso Angbo Hang – overseeing the realm of Athraya with his seat of power situated at Pomajong.

4. Thindolung Khoya Hang – ruling over Yangwarok with his capital at Hastapojong Yiok.

5. Ye nga so Papo Hang – presiding over Panthar, with his capital divided between Yashok and Phedim.

6. Shengsengum Phedap Hang – holding sway over Phedap and commanding from his noble capital Poklabung.

7. Mung Tai Chi Emay Hang – reigning over Ilam with a regal residence at Phakphok.

8. Soiyok Ladho Hang – governing Miklung (Choubise) and holding court at Shanguri Yiok.

9. Tappeso Perung Hang – presiding over Thala with a strong center at Thala Yiok.

10. Taklung Khewa Hang – ruling Chethar with his regal abode at Yiok.

These ten Limbu rulers, each holding sway over specific territories and fortified capitals strategically located within the region, exerted a profound influence on the history and governance of Limbuwan throughout the duration of their impressive reigns. By skillfully navigating the complex political landscape of their era, these rulers not only solidified their own legacies but also left an indelible mark on the development of Limbuwan, shaping its societal structure and administrative framework for generations to come. Through their astute leadership and strategic decisions, they successfully established a blueprint for governance that would guide subsequent rulers in managing the affairs of Limbuwan with efficiency and foresight, ensuring the continuity of their established institutions and policies long after their reigns had concluded.

Ten kings of Limbuwan, including the renowned King Mung Mawrong Hang, played a crucial role in shaping the history of the region during the 7th century. King Mung Mawrong Hang rose to prominence in the terai lands of Limbuwan, specifically in the present-day Sunsari, Morang, and Jhapa areas. His influence extended to the region as he initiated the clearing of vast forested areas, particularly in what is now known as Rangeli, situated to the east of Biratnagar, where he established a thriving town.

The landscape of Limbuwan was characterized by the rule of the ten kings who held sway over the terai lands through the Kingdom of Ilam and the Kingdom of Bodhey (Choubise). In response to King Mawrong’s growing power, these ten kings united their forces and launched a collective effort to expel King Mawrong from the Rongli area.

Despite being forced into exile in Tibet and seeking refuge in Khampa Jong, King Mung Mawrong Hang held steadfast to his ambition of asserting his dominion over all of Limbuwan. This period in Limbuwan coincided with the reign of King Tsrong Tsen Gempo in Tibet, offering Mawrong the opportunity to forge an alliance with the Tibetan King and rally support from the Bhutia tribes of Khampa Jong in preparation for an assault on Limbuwan from the north.

The ensuing conflict between King Mawrong and the ten kings of Limbuwan culminated in a decisive battle that unfolded across the treacherous terrains of Hatia, Walungchung, and Tapkey passes in the Himalayas. Despite a valiant effort, the ten kings of Limbuwan were defeated, paving the way for King Mawrong to ascend as the supreme ruler of Limbuwan. While the ten kings retained their positions, they now operated under the overarching authority of King Mung Mawrong Hang, ensuring the continued governance of their respective territories.

Additionally, King Mawrong instituted a vibrant festival known as “Namban” among the Yakthung people, commemorating the bountiful harvest annually in the final week of December. This festival not only fostered unity and celebration among the communities but also stood as a testament to King Mawrong’s lasting impact on the cultural traditions of the region.

The legacy of King Mung Mawrong Hang endured even after his passing, as one of his trusted ministers, King Mokwanhang, assumed the throne due to the absence of a direct male heir. Following a transitional period, King Uba Hang emerged as a prominent figure in the Limbuwan region, further shaping its political landscape and cultural heritage.

The era of the Lasahang dynasty

During the reign of the Lasahang dynasty, King Uba Hang emerged as a prominent figure following the passing of King Mawrong Hang. His influence and fame extended throughout the Limbuwan area as he managed to subjugate the previously held territory of King Mokwansan Hang, eventually ascending to the throne as King. Noteworthy for his introduction of a new belief system among the Yakthung people, King Uba Hang ushered in significant changes to the region’s religious practices, particularly within the mundhum faith. Encouraging his subjects to offer floral tributes and fruits to the revered spirit of Tagera Ningwafumang, he abolished the tradition of blood sacrifices.

Amid his rule, he commissioned the construction of the formidable Chempojong fort and palace located in Ilam. King Uba Hang also instituted the Tong Sum Tong Nam festival, a triennial celebration held in honor of the Limbu Ancestor goddess Yuma Sammang and the supreme deity Tagera Ningwafumang. This vibrant festival, known as Trisali Puja in Nepali language, continues to be observed in the Panchthar district of Nepal to this day, symbolizing the enduring legacy of the king’s devotion to Yuma Mang and the propagation of Yumaism, a religious philosophy ingrained in the fabric of Limbuwan culture.

Following the era of King Uba Hang, his successor, King Mabo Hang, assumed the mantle of leadership in Limbuwan. Revered by many as the embodiment of divinity, King Mabo Hang, known as Thakthakkum Mabo Hang, commanded respect and admiration across the region. Relocating the capital from Chempo Jong in Ilam to Yasok Jong in Panchthar, he continued the propagation of Yumaism as the official state religion, establishing a legacy of spiritual unity and cultural cohesion.

Subsequent to King Mabo Hang’s reign, his son, King Muda Hang, acceded to the throne but faced challenges in maintaining centralized rule over the ten districts of Limbuwan. The ten district rulers asserted their independence, sparking a period of disarray and fractious governance within Limbuwan. Consequently, the once-unified territory of Limbuwan disintegrated, diminishing the Lasa dynasty’s dominion to solely Panchthar area and the southern precincts of Limbuwan, marking a turbulent phase in the realm’s history.

In the tumultuous aftermath of the disintegration, King Muda Hang’s son, King Wedo Hang, assumed the kingship, presiding over the kingdom from Hellang palace in Panthar. Engaged in conflicts with Chief Nembang Hang, a formidable adversary, the king faced treacherous schemes and ultimately met his demise through assassination plots orchestrated by his enemies. With the treacherous assassination of King Wedo Hang, Queen Dalima, the sister of Chief Nembang, bore the legacy of her late husband, carrying a child conceived from their union, precipitating a shift in power dynamics within the realm.

The transition of power led to the ascendancy of King Chemjong Hang, the fifth monarch of the resilient Lasa dynasty. Born in the ancestral Chempojong palace in Ilam, King Chemjong Hang’s early life was shrouded in secrecy and intrigue, as his mother concealed his identity, donning the guise of a girl to safeguard him from potential threats. Transforming into a discerning and robust individual, King Chemjong traced the trails of his father’s followers in the northern reaches of Limbuwan, cultivating alliances with local chieftains to fortify his position.

Capitalizing on a momentous opportunity during a festive occasion at Hellang palace, King Chemjong revealed his true identity to the assembled chiefs, eliciting their acknowledgment and support as the legitimate heir to the late King Wedo Hang. Garnering the name Chemjong Hang in homage to his birthplace, he embarked on a mission to reunite the disparate fragments of Limbuwan, successfully extending his rule over territories encompassing Panchthar, Illam, Dhankuta, Sunsari, Morang, and Jhapa. In his pursuit for unity and sovereignty, King Chemjong Hang played an instrumental role in shaping the intricate tapestry of Limbuwan’s history, bridging divides and fostering a sense of shared destiny among its inhabitants.

The era of King Sirijunga Hang

During the era of King Sirijunga Hang (880–915), a significant figure in the history of Limbuwan, the political landscape was shaped by intricate power plays and dynamic shifts of authority. King Galijunga Hang held sway over the Yangwarok kingdom, a pivotal domain within Limbuwan during the reign of King Uba Hang, who acted as Galijunga’s superior at that time. As the influence of King Muda Hang waned, creating a power vacuum in Limbuwan, it was the rise of Sirijunga, the grandson of King Galijung, that proved instrumental in filling the void within the northern regions of Limbuwan.

Central to the unification of northern Limbuwan was King Sirijunga’s remarkable ability to exert control over the Yakthung chiefs, consolidating power under his firm grasp during the tumultuous period of King Muda Hang’s instability. Recognized for his military prowess and strategic vision, Sirijunga succeeded in subduing rival factions, thereby ushering in an era of relative peace and unity.

The enduring legacy of King Sirijunga extends beyond his military achievements, encompassing notable architectural endeavors such as the construction of two formidable forts—Sirjunga fort in modern-day Terhathum district and Chainpur fort in Sankhuwasabha district. These imposing structures, bearing the name of their visionary creator, stand as enduring testaments to Sirijunga’s commitment to fortifying his realm against external threats.

Moreover, King Sirijunga’s influence transcended the realm of warfare and construction to encompass cultural innovation. Renowned for his cultural contributions, Sirijunga is credited with inventing the Limbu script, a pivotal development that revolutionized communication among the Yakthungs. According to Limbu religious texts, the goddess Nisammang bestowed upon Sirijunga the sacred knowledge of writing during a divine encounter at mount Phoktanglungma, tasking him with disseminating this priceless gift among his people. This pivotal event marked the advent of the written word in Limbuwan, profoundly shaping the cultural and intellectual landscape of the region.

Among the enduring reforms instituted by King Sirijunga, the Kipat land system stands out as a hallmark of his visionary governance. By dividing lands among clan and village chiefs under the Kipat system, Sirijunga empowered local leaders with authority over their territories, fostering a sense of communal ownership and solidarity. This innovative land reform ensured that chiefs held exclusive rights over their lands, prohibiting the sale of ancestral territories to outsiders and non-clan members. Additionally, the Kipat system enforced egalitarian principles by mandating equal land distribution among heirs and gender equity, stipulating that all sons and unmarried daughters receive a fair share of inherited lands.

Furthermore, King Sirijunga’s establishment of village councils, known as Chumlung, exemplified his commitment to participatory governance and inclusive decision-making. The chief’s role as the presiding authority in clan and village affairs underscored the importance of local leadership in maintaining social cohesion and resolving disputes. Through the implementation of the Kipat land system and the governance structure of Chumlung councils, Sirijunga laid the foundation for a resilient and self-sustaining social order in Limbuwan.

The enduring influence of the Kipat land system devised by King Sirijunga reverberated not only within Limbuwan but also across neighboring Kirant territories in Nepal. The principles of communal land ownership and non-transferability of Kipat lands resonated with various ethnic groups, including the Kirant Rai, Kirant Sunuwar, and Tamang communities, who embraced this innovative land tenure system. Through successive rulers, the legacy of Sirijunga’s Kipat system endured, ensuring that the unique customs and laws governing land ownership remained integral to the cultural identity of the Limbu people and their Kirant neighbors.

The period of the ten kings after King Sirijunga

During the period following the reign of King Sirijunga, Limbuwan experienced a significant shift in governance as the ten kingdoms of Limbuwan rose to power, ruling collectively from 915 to 1584. This era of the ten kings marked a pivotal moment in the history of Limbuwan, shaping the nation’s identity, culture, language, and ethnicity. The establishment of these kingdoms, stemming from the revolutionary events of the 6th century, laid the foundation for a period of stability and regional development in Limbuwan.

Among the kingdoms that emerged during this time, the Morang Kingdom in the lowlands of Limbuwan, encompassing present-day terai lands of Sunsari, Morang, and Jhapa, gained prominence. The evolution of Morang Kingdom as a distinct entity began under the leadership of King Mung Mawrong Hang, who navigated the territory towards autonomy from neighboring kingdoms like Ilam and Mikluk Bodhey. By the early 1400s, Morang Kingdom solidified its boundaries along the Kankai river to the east, the Koshi river to the west, the Shanguri fort to the north, and Jalal garh in the south India, establishing a sovereign domain.

The ascendancy of King Sangla Ing in Morang Kingdom ushered in a new era of leadership, marking the first native king to reign in the lowland Limbuwan region in centuries. His strategic alliances with fellow Limbuwan rulers fostered a sense of unity and cooperation among the kingdoms, enabling mutual growth and protection. King Sangla Ing’s royal seat at Varatappa became a symbol of the kingdom’s stability and prosperity, resonating with the rich traditions and history of the land.

Following King Sangla Ing’s reign, his son Pungla Ing, later known as Amar Raya Ing upon embracing Hinduism, continued the legacy of leadership in Morang Kingdom. His conversion and name change reflected the cultural dynamics at play during this transformative period, highlighting the interconnectedness of religious beliefs with political authority. Under Amar Raya Ing’s rule, Morang Kingdom witnessed further advancements and integration within the broader Limbuwan community, solidifying its position as a key player in the region’s historical narrative.

The Sanglaing dynasty kings

The Sanglaing dynasty kings, including King Sangla Ing, who was the first ruler of the Ing dynasty, paved the way for a line of monarchs that included illustrious names such as King Pungla Ing, also known as Amar Raya Ing, and King Kirti Narayan Raya Ing, who left a lasting legacy in the history of the Morang Kingdom. Alongside them stood King Ap Narayan Raya Ing, King Jarai Narayan Raya Ing, King Indhing Narayan Raya Ing, and King Bijay Narayan Raya Ing, who proved to be the final monarch of the Ing dynasty, leaving behind a remarkable tale of friendship and power struggles.

Towards the end of the Ing dynasty’s reign, King Bijay Narayan forged a close bond with the ruler of Phedap, Murray Hang Khebang, leading to significant developments in the Morang Kingdom’s history. It was during this era that the foundation of Bijaypur town was laid, with King Bijay Narayan’s vision and friendship with Murray Hang Khebang shaping the landscape of the kingdom. Bijaypur town, located near present-day Dharan City, emerged as the capital of the Morang Kingdom and Limbuwan until the year 1774, highlighting the enduring impact of King Bijay Narayan’s decisions.

As King Bijay Narayan’s influence grew, he appointed Murray Hang Khebang as his prime minister, marking a pivotal moment in the political landscape of Limbuwan. The prime ministerial title became a hereditary position for Murray Hang’s descendants, emphasizing the enduring legacy of King Bijay Narayan’s rule. This move solidified King Murray Hang’s position as the first prime minister of Limbuwan and the second king to bear the Hindu title of “Raya,” showcasing the evolving power dynamics within the kingdom.

However, tensions soon arose between King Bijay Narayan and his prime minister Murray Hang Khebang, leading to a tragic turn of events that altered the course of history. The king’s accusations against Murray Hang, culminating in the prime minister’s alleged crime of raping the king’s daughter, ultimately resulted in a royal decree of death for Murray Hang. In response, Murray Hang’s son, King Bajahang Khebang of Phedap, sought retribution for his father’s demise, seeking assistance from King Lohang Sen of Makwanpur to overthrow the Morang Kingdom.

In a fateful confrontation in 1608, the forces of Makwanpur, led by King Lohang Sen, successfully conquered Bijaypur, leading to the demise of both King Bajahang Khebang and King Bijay Narayan. Following these events, King Lohang Sen appointed Bidya Chandra Raya Khebang, the grandson of Murray Hang and son of Bajahang Khebang, as the new prime minister of the Morang Kingdom, granting him autonomy to govern the region. With a new ruler in place, the kingdom underwent a period of transition as Bidya Chandra sought validation as the rightful King of Limbuwan, securing recognition from the Dalai Lama in Lhasa and solidifying his authority over Phedap and Morang.

This tumultuous era also saw the rise of various other kingdoms in Limbuwan, each ruled by its own regents, emphasizing the intricate tapestry of power and politics that defined this vibrant region during that era.

The era of divided Limbuwan (1609–1641)

The era of divided Limbuwan (1609–1641) was a tumultuous period marked by significant political upheaval and shifting alliances within the region. It all began with the demise of King Bijay Narayan Sanglaing of Morang, which triggered a chain of events leading to a fierce war of revenge orchestrated by the King of Phedap. This conflict ultimately resulted in the conquest of the Morang Kingdom of Limbuwan by LoHang Sen of Mokwanpur, a pivotal moment that shattered the longstanding unity among the Limbuwan states.

The absence of a cohesive Limbuwan association further exacerbated the fracturing of the region, as only a handful of the ten kingdoms chose to align themselves with the Sen king, recognizing him as their superior. Meanwhile, in the year 1641, a significant development occurred with the ascension of King Phuntsog Namgyal to the throne of Sikkim. This change in leadership proved to be a turning point, as independent Limbu kings from Tambar, Yangwarok, Panthar, and Ilam Kingdoms decided to forge alliances with the new Sikkimese ruler.

This strategic realignment effectively cleaved Limbuwan in two, with the eastern and northern Limbuwan kingdoms pledging their allegiance to the kings of Sikkim. From King Phuntsog Namgyal’s coronation in 1641 until the year 1741, this division persisted, with the Sikkimese monarch solidifying his influence over a significant portion of Limbuwan. The era of divided Limbuwan thus became a defining chapter in the region’s history, characterized by intricate political dynamics and a reshuffling of power structures that would have enduring implications for years to come.

The era of the Namgyal dynasty in eastern and northern Limbuwan (1641–1741)

The era of divided Limbuwan (1609–1641) was a tumultuous period marked by significant political upheaval and shifting alliances within the region. It all began with the demise of King Bijay Narayan Sanglaing of Morang, which triggered a chain of events leading to a fierce war of revenge orchestrated by the King of Phedap. This conflict ultimately resulted in the conquest of the Morang Kingdom of Limbuwan by LoHang Sen of Mokwanpur, a pivotal moment that shattered the longstanding unity among the Limbuwan states.

The absence of a cohesive Limbuwan association further exacerbated the fracturing of the region, as only a handful of the ten kingdoms chose to align themselves with the Sen king, recognizing him as their superior. Meanwhile, in the year 1641, a significant development occurred with the ascension of King Phuntsog Namgyal to the throne of Sikkim. This change in leadership proved to be a turning point, as independent Limbu kings from Tambar, Yangwarok, Panthar, and Ilam Kingdoms decided to forge alliances with the new Sikkimese ruler.

This strategic realignment effectively cleaved Limbuwan in two, with the eastern and northern Limbuwan kingdoms pledging their allegiance to the kings of Sikkim. From King Phuntsog Namgyal’s coronation in 1641 until the year 1741, this division persisted, with the Sikkimese monarch solidifying his influence over a significant portion of Limbuwan. The era of divided Limbuwan thus became a defining chapter in the region’s history, characterized by intricate political dynamics and a reshuffling of power structures that would have enduring implications for years to come.

The era of the Sen dynasty in western and southern Limbuwan (1609–1769)

During the expansive reign of King Kamadatta Sen from 1761 to 1769, marked by a mixture of political intrigue and diplomatic finesse, his strategic maneuvers and alliances paved the way for a period of stability and prosperity in the region of Limbuwan. As he ascended to the throne amidst doubts surrounding his legitimacy due to his status as an illegitimate son, King Kamadatta faced challenges from within his own court, notably from his prime minister, Bichitra Chandra Raya Khebang of the Phedap Kingdom. The tensions escalated as the power struggle intensified, leading to a momentous clash of personalities that would shape the fate of the Morang Kingdom.

Despite initial skepticism regarding his rule, King Kamadatta proved himself to be a remarkable leader, earning the loyalty and respect of his subjects through his inclusive policies and visionary governance. He went on to redefine the social structure of Limbuwan by uniting the various Limbu kings, ministers, and chiefs under his banner, effectively integrating them into his royal lineage and fostering a sense of familial camaraderie. Moreover, his marriage to Princess Thangsama Angbohang not only solidified political alliances but also symbolized a commitment to regional harmony and cooperation.

Furthermore, King Kamadatta’s astute diplomatic efforts extended beyond the borders of Limbuwan, as he forged amicable relationships with neighboring states such as Bhutan, Sikkim, Tibet, and even Bhaktapur, demonstrating a keen interest in regional cooperation and mutual understanding. He skillfully navigated the complex web of regional politics, garnering praise for his ability to balance power dynamics and maintain stability in an ever-changing landscape. By extending invitations to foreign dignitaries, including representatives from Bhutan and Bhaktapur, he showcased his commitment to fostering diplomatic ties and promoting peace in the region.

As King Kamadatta’s reputation grew, so did his popularity among the people of Limbuwan, who began to view him as a benevolent and visionary ruler capable of steering the kingdom towards a brighter future. His emphasis on autonomy for the Limbu people, coupled with his unwavering support for customary practices such as the Kipat land system, endeared him to his subjects and solidified his position as a revered monarch. Despite facing internal dissent and external threats, King Kamadatta’s legacy as a unifier, diplomat, and protector of Limbuwan’s traditions remains etched in the annals of history, symbolizing an era of both challenges and triumphs.

During the era of divided Limbuwan, King Buddhi Karna Raya Khewang of Morang (1769–73) found himself faced with a significant challenge after the assassination of Kama Datta Sen. Upon assuming the throne in Bijaypur, he became the last king of Morang and Limbuwan. However, the tragic news of King Kama Datta Sen’s demise caused a rift among the states comprising Limbuwan and their allies, leading to the disintegration of their unity. Subsequently, the kings of Limbuwan withdrew their allegiance from Buddhi Karna, leaving him in dire need of capable ministers and chiefs to assist him in governing Morang and the broader Limbuwan region. Realizing the urgency of the situation, Buddhi Karna dispatched emissaries to seek support from King Shamo Raya Chemjong of the Miklung Bodhey Kingdom.

During this tumultuous period, various other rulers played instrumental roles in the fate of Limbuwan:

– King Shridev Roy Phago — the esteemed ruler of the Maiwa Kingdom

– King Raina Sing Raya Sireng — the monarch of the Mewa Kingdom

– King Ata Hang — the revered king presiding over the Phedap Kingdom

– King Subhawanta Libang — the sagacious ruler of the Tambar Kingdom

– King Yehang — the sovereign of the Yangwarok Kingdom

– King Thegim Hang — the respected king governing the Panthar Kingdom

– King Lingdom Hang — the monarch of the illustrious Ilam Kingdom

In the midst of these intricate alliances and shifting loyalties, King Shamo Raya Chemjong emerged as a key figure entrusted with leading the Kings of Limbuwan and chiefs of Limbuwan in the signing of a crucial treaty with the King of Gorkha. Not only was Shamo Chemjong an influential figure in the political landscape, but he also assumed the role of prime minister of the Morang Kingdom, effectively governing Morang during Buddhi Karna’s absence as he sought assistance from the British. Notably, the king of Ilam, the son of King Lingdom, was the final Limbuwan ruler to formalize a treaty with the King of Gorkha.

The Limbuwan Gorkha War eventually concluded in 1774 after an agreement was reached between the King of Gorkha and the Kings of Limbuwan and their ministers convened in Bijaypur, Morang. This marked a crucial turning point in the history of Limbuwan and its relationship with the surrounding regions.

The era of the Shah dynasty in Limbuwan

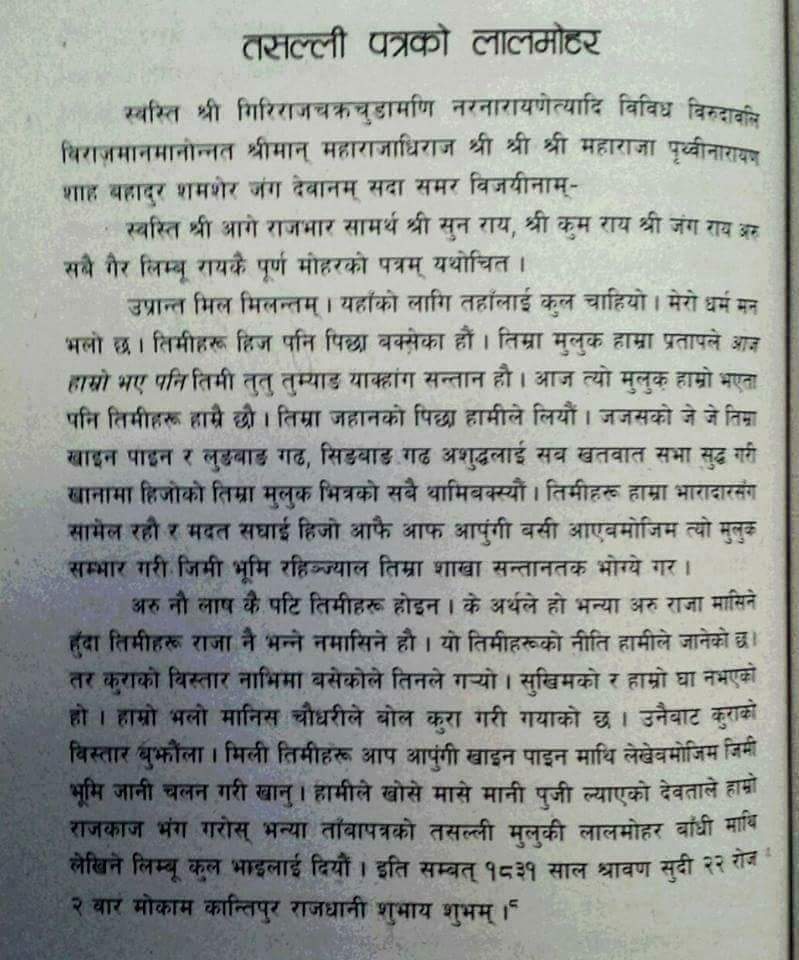

The era of the Shah dynasty in Limbuwan marked a significant chapter in the region’s history, particularly during the reign of King Prithivi Narayan Shah from 1768 to 1775. King Prithivi Narayan’s pivotal role was the assimilation of Limbuwan lands into his expanding Gorkha Kingdom, ultimately leading to the formation of the unified Nepal we know today. This integration reshaped the administrative landscape, transforming the former ten kingdoms of Limbuwan into seventeen districts under Gorkha rule. The transition also saw the erstwhile Limbu monarchs take on the position of subbas under the new Gorkha king, with gradually diminishing autonomy over time.

Central to Limbuwan’s societal structure was the unique Kipat system that conferred ownership rights over various resources, including rice fields, forests, and mineral deposits. While the rest of Nepal operated under the “Raikar” land ownership system, Limbuwan retained the traditional “Kipat” system, sanctioned by the state. The Gorkha king’s policy of granting autonomy to Limbuwan served a dual purpose – securing the loyalty of the Limbu people and facilitating strategic expansion into neighboring territories like Sikkim. This shrewd maneuver exemplified the Shah rulers’ divide-and-rule strategy, leveraging alliances while ensuring compliance through mutual agreements like the Gorkha-Limbuwan Treaty of 1774.

The treaty, symbolized by the solemn oath taken on “Noon pani” (saltwater), showcased the mutual commitment between the Gorkha representatives and the Limbu ministers. The ritualistic swearing epitomized the intertwined destinies of the two parties – likening the Gorkhas to water and the Limbus to salt, interdependent yet distinct. Through this symbolic act, both sides pledged perpetual fidelity, with the promise that any betrayal would result in catastrophic consequences foretold by the divine retribution associated with breaking such a sacred oath.

The agreement encapsulated in the Lal Mohor further solidified the bond between the Gorkha Kingdom and the Limbu territories, emphasizing protection, progress, and mutual respect. The Gorkha king’s acknowledgment of the Limbu rulers as extended family members underscored the inclusive approach adopted to ensure harmonious governance. This diplomatic accord not only delineated boundaries and responsibilities but also laid the groundwork for collaborative coexistence based on trust and shared prosperity.

In response to the Gorkha-Morang alliance, other Limbu rulers, including those from Mewa, Phedap, and Tambar kingdoms, also joined forces under the same terms outlined in the treaty. The unification of diverse Limbu principalities signaled a collective resolve to stand united against external threats while embracing the benefits of a consolidated front. However, certain factions within the Phedap Kingdom expressed dissent, challenging the legitimacy of Gorkha encroachment and rejecting the terms dictated by the salt-and-water pact. This internal strife exemplified the complexities of political allegiances and the delicate balance between sovereignty and subjugation within the context of changing regional dynamics.

The aftermath of the Limbuwan-Gorkha War witnessed a transformative shift in power dynamics, with most Limbu territories aligning themselves with the Gorkha Kingdom to forge a cohesive entity. Yet, pockets of resistance persisted, notably in the Kingdom of Yangwarok and Ilam, echoing the nuanced negotiations of sovereignty and self-determination that colored the broader narrative of territorial realignment and consolidation in the tumultuous landscape of 18th-century Nepal.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Limbuwan